Understanding rebalancing and the art of selling

What people are scared to tell you about selling

Investors speak often and extensively about when, how, and why they buy businesses. However, people tend to avoid speaking about when to sell, although it may be as interesting a topic as when to buy.

I’ve been reading a market commentary today about a fund that trimmed some positions during the tariffs panic to increase some others. They trimmed those positions that had fallen the least and increased those who went down the most. Of course, after the flash recovery, they had some better upside in those businesses; they increased positions, only because, as the risk “faded”, the rebound was stronger.

At a moment during the commentary, they were arguing that the positions they sold had barely fallen during the panic, so they sold at their sell price. But then you should be thinking: if they fell slightly, and still you sold at your “sell price”, why did you have that position? If you have a price, and the business reaches its price, you should sell, right?

Enough about what they said. Let me explain to you how I’ve built my process over the years. I’m not saying it’s perfect, but it works for me and my personality. Investing is often said to be an art rather than a science. A craft for many. So there’s no universal truth in it, and you have to find the practices that work better for you, so you can maximize your strengths and minimize your weaknesses.

Before we jump into the selling, I think it is necessary to clarify when to buy. In my opinion, rational investing occurs only when you buy something that you consider to be at a discount to its fair value. Hence, I assume hereafter that, if you have bought any business, you think logically that it is worth more than the price you paid.

There are two types of businesses you could buy: good businesses and poor businesses. Let’s start with the poor businesses.

Poor businesses:

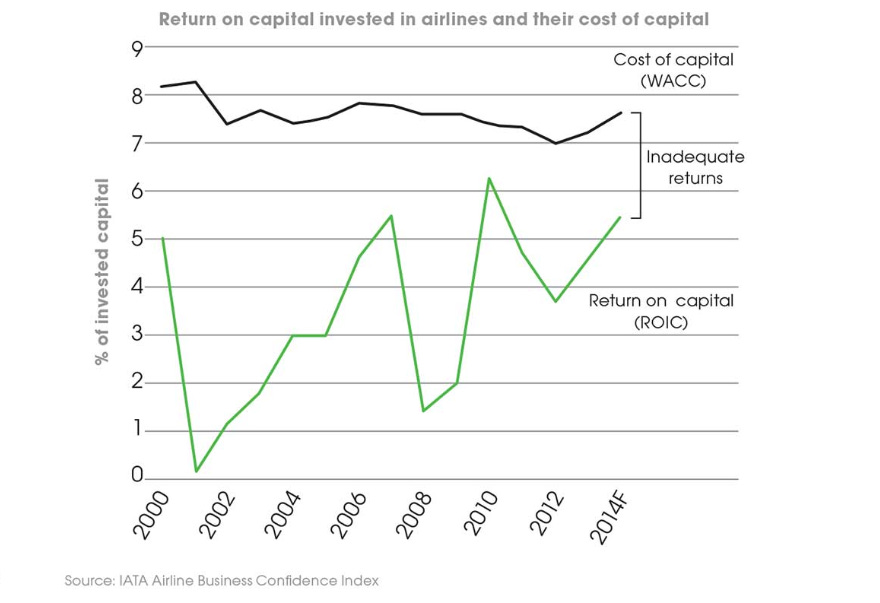

These businesses don’t deliver a return over their cost of capital, meaning that they destroy value over time. Said otherwise, they are likely to deliver poor returns over time, and you are probably better off investing somewhere else. One clear example of these businesses is airlines, since they tend to lose money over a whole business cycle.

Since these are not good businesses, and since we buy companies to become their owners, we should avoid these stocks. However, every now and then, some cigar butts, as Warren Buffett used to describe them, arise and are probably very attractive from a risk/reward point of view.

Say, for instance, that you find a company whose upside is 100%, it presents a good and plausible catalyst, and the downside looks protected because the company’s enterprise value equals its cash. Yeah, I know this is an unlikely scenario, but it’s only for the sake of the example.

In this case, if you think that the company’s value is 1$ and currently trades at 0.50$, as soon as the share price goes to 1$, you should be out of your position. You have a price target, and you don’t care about anything else. It is tempting to keep the position, especially if it looks like the share price has some “momentum”, but that’s not our game. We’re here to approach investing rationally.

Why would I sell immediately after it reaches our calculated value?

Because we don’t want to be long-term holders of bad businesses, since, by definition, they will deliver poor returns to long-term owners.

Good businesses:

But what about those outstanding businesses that are so hard to find at reasonable prices?

At the beginning of my investing journey, I was on the side of never selling good businesses. I read this idea from Keith-Ashworth Lord, who argues that it is difficult enough to find a good business at a good price as to be doing it often. If you find a good company, you stick to it, through thick and thin.

Over time, my taste has been evolving towards what Vitaliy Katsenelson calls Active Value Investing. Yes, it is difficult to find good companies at good prices, but even great companies don’t deserve an infinite price. But I’m not willing to sell them slightly above my fair estimate either, since good companies tend to outperform on the upside.

For this reason, I don’t sell good companies when they reach my estimated fair value. Instead, I want the share price to discount one year of expected returns to today, and on top of that, I want the share price to absorb the impact of taxes as well.

Let’s see an example. Say that my fair price for a business’ share is 1$, and I expect it to grow its value to 1.1$ during the next year. Well, in that case, I want the share price to be 1.1$ today before selling. On top of that, I will calculate the effect of taxes.

Say that I bought the company with a 20% discount, that is, 0.80$. If the tax rate is 30%, I want to sell at 1.1$ net of taxes. Hence, I would have to sell at 1.228$ (I would pay tax for 1.228$ - 0.80$ = 0.128$). In this example, with this tax rate, the premium I’m asking for a company growing at 10% its value is 22%. It may look aggressive, but if someone wants to buy a good business from me, they have to pay a premium!

About trimming when a stock goes up, but doesn’t reach your target price:

Then I see many people trimming when a stock goes up 10%, to reallocate those funds to a stock that has gone down 3%. Let me give you my honest opinion about that: it is worthless.

Those investors usually argue that they add some performance because of that activity. Well, I’m very skeptical about that. But I’m sure about something: it triggers taxes. And that’s unavoidable.

Maybe they don’t consider taxes within their performance, but they should, if they want to increase their capital.

They can also argue that they can sell something to harvest some losses. Well, then in a given year your activity has helped you gain a total of 0$!! And you are likely restricted from buying back what you sold to harvest losses. From a particular investor's point of view, it doesn’t make sense, in my opinion.

Instead, I advocate being active when you need to be active: that is, when someone is willing to overpay for your good business, or to pay a fair price for the cigar butt you bought. The rest of the time, your time is better spent researching new businesses or the ones you currently hold.